- Introduction

- How Can It Be Done?

- You can Have Your Cake and Eat It Too (mostly)

- Still Not a Silver Bullet

- Why I Will Sign Up

- References and Further Reading

Introduction

One of the most effective ways to combat an epidemic is contact tracing. Selectively quarantining people may not be as effective as the broad quarantining of an entire population, but it has many benefits, such as reducing the impact on the economy. This is especially important as many people do not have enough savings to survive for long periods in lockdown.

How Can It Be Done?

Currently, most contact tracing is done by "interviewing" a diagnosed patient to determine where they were and who they were in contact with. Although this requires no additional infrastructure to work, it is very error-prone. The patient may also need to recall this information over a long period of time. This is especially problematic in urban areas where diseases spread the most quickly, and people live and work closely together. Although this system was proven to help in previous outbreaks such as the Ebola outbreak in 2014[1] and the SARS outbreak in 2003[2], COVID-19 is much more infectious and widespread. We need a different solution.

An enticing alternative is automated contact tracing through cellphones. Right now, especially in the US, there is a very high penetration of smartphones with a variety of sensors and wireless communication capabilities. People also keep these devices with them when they leave their homes. This combination makes these devices ideal for contact tracing. However, there is one serious concern that needs to be addressed before a solution is implemented: privacy. The most obvious way to do contact tracing through smartphones is tracking everyone's location at all times. To many people, this would be an unacceptable solution, even if it has the potential to drastically mitigate the virus's spread. It is not only a question of who has access to the data; hackers could also infiltrate such a system and track people for malicious purposes. More authoritarian countries such as China can sidestep the privacy issue, but others must find another way to gain the consent of users.

You can Have Your Cake and Eat It Too (mostly)

Two long-time rivals, Apple and Google, partnered up to create a solution that preserves the privacy of individuals while providing many of the same benefits as a centralized system[3]. Their system employs a combination of Bluetooth and cryptographic techniques to hide the identities of users while providing many of the same features a centralized tracking system would provide. However, a system like this is far more complex than logging location data on a server. Instead, a user's phone will send out signals to nearby devices. MIT's solution[4] likened them to "chirps". Whenever anyone's device hears these "chirps", they are stored. Let's imagine a hypothetical scenario to illustrate how the tracing solution would work.

When your device is updated, you are given the option to consent to the service. After you activate the service, your device will create a unique tracking key. This is what identifies your device and it will never be shared, not with other devices or a central server. Every day you use your device, it will create a daily tracking key.

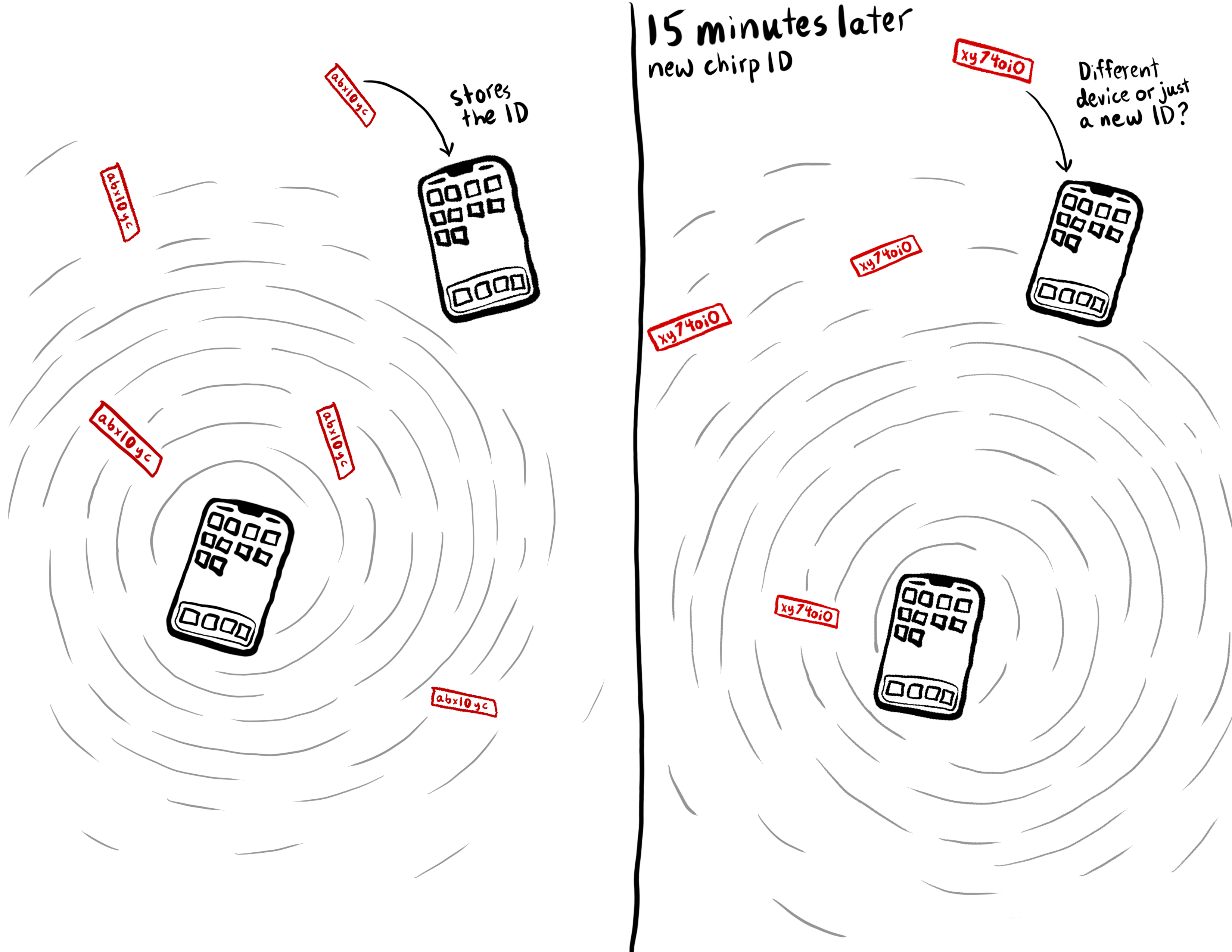

You then decide you need to go grocery shopping since restaurants are closed. Your device automatically connects to and communicates with other nearby devices that have the tracing software activated. It sends them a "Rolling Proximity Identifier" which is generated from the daily tracking key. We will call them "chirps" and they contain a unique identifier. These IDs are stored on all devices that hear them. The IDs of the chirps that your device emits change every 15 minutes. Your device is simultaneously listening and storing chirps from other devices.

Because the chirps change so often, the device they come from is very hard to track over long periods of time. Creating the chirp IDs in this multi-step process also increases security.

Because the chirps change so often, the device they come from is very hard to track over long periods of time. Creating the chirp IDs in this multi-step process also increases security.

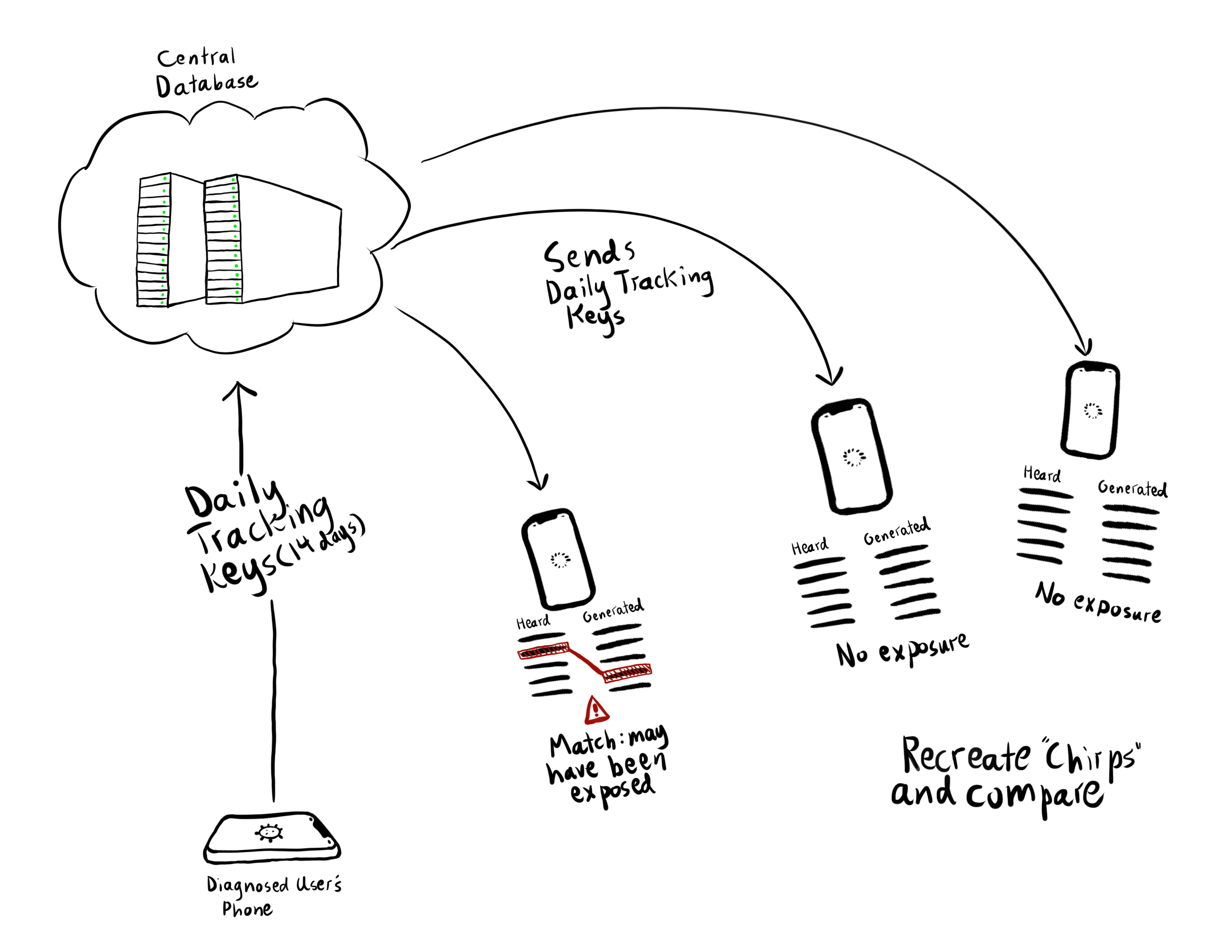

Continuing with the story, somebody who activated the service contracts COVID-19. They will send their daily tracking keys for the past two weeks to a central database. These keys don't store any personal information. If you have the service on, you will receive these keys. Your device will automatically recreate the IDs of the chirps this anonymous person broadcasted. If the device recalls "hearing" them then you were in close contact with that person sometime within the past two weeks.

The patient's privacy will be preserved since nobody will know who's chirps their devices heard (mostly...keep reading!).

The patient's privacy will be preserved since nobody will know who's chirps their devices heard (mostly...keep reading!).

Still Not a Silver Bullet

Although this system is a huge step up from GPS-based location tracking, there are still some concerns related to privacy. Due to the increased complexity of the system, there are also technical challenges that need to be overcome.

Ashkan Soltani, a former FTC chief technologist describes a way someone could determine who was infected[5]. A malicious user could manually or automatically(possibly through computer vision) assign the names of people to the chirps their devices emitted. Then, when they generate the IDs of the chirps from daily tracking keys sent by the server, they can identify who was infected if they had assigned a name to the chirp earlier. Employees at Apple and Google couldn't come up with a solution on the spot but responded that a surveillance camera at a clinic entrance would be more effective. Either way, a large scale attack is still impossible.

Also, ad services will be barred from using the tracing API. It is reasonable to wonder if stores will attempt to record location data. It is definitely possible using the same technique Soltani suggested, but tracking the transactions is much more practical and is already in practice.

The biggest security hole in the system is when someone uploads their daily tracking keys. Due to the nature of how information is sent through the internet, IP addresses are traceable. An organization can use this to find out who uploaded the keys. However, it's only possible if that organization has a directory of users and the IP addresses of their phones. Apple and Google have said their solutions will not record IP addresses for privacy, but if they wanted to it is possible. It will be a matter of policy, not a technical impossibility.

There is also the challenge of detecting proximity using Bluetooth. It is done through signal strength, but it can be obscured by things such as a person's body or the cloth of a pocket. Apple and Google said they are working on ways to circumvent these obstacles by using other sensors on a phone. For example, if a phone detects a walking gait using accelerometers and darkness using a light sensor, the phone is likely in a pocket. This is can be used to correct proximity calculations.

There are also issues with service penetration. Many devices may be too old to support all the sensors required. Some people might not have devices at all. This system will undoubtedly reveal more inequalities in our society. People who work low-pay, high-risk jobs might not be able to afford a device with the capabilities required, especially during this time. This can be mitigated by suggesting some low-cost tracing-capable devices. Also, the system is opt-in which is the right thing to have, but it will likely reduce the system's effectiveness. There is promising research done by Oxford University that if 60% or less of users opted in, the system would be still effective[6].

Why I Will Sign Up

The system is far from perfect. Nobody should expect it to be. However, whenever I have the option to activate the service, I will because the risks are relatively minor. In times of crisis, there are always some sacrifices that need to be made. Thanks to the work by the employees and Apple and Google, this sacrifice has become a lot easier to swallow.

References and Further Reading

- Contact tracing performance during the Ebola epidemic in Liberia, 2014-2015

- Epidemic Models of Contact Tracing: Systematic Review of Transmission Studies of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome

- Apple | Privacy-Preserving Contact Tracing

- Bluetooth signals from your smartphone could automate Covid-19 contact tracing while preserving privacy

- Does Covid-19 Contact Tracing Pose a Privacy Risk?

- Digital contact tracing can slow or even stop coronavirus transmission and ease us out of lockdown